— The Legend —

— The Legend —

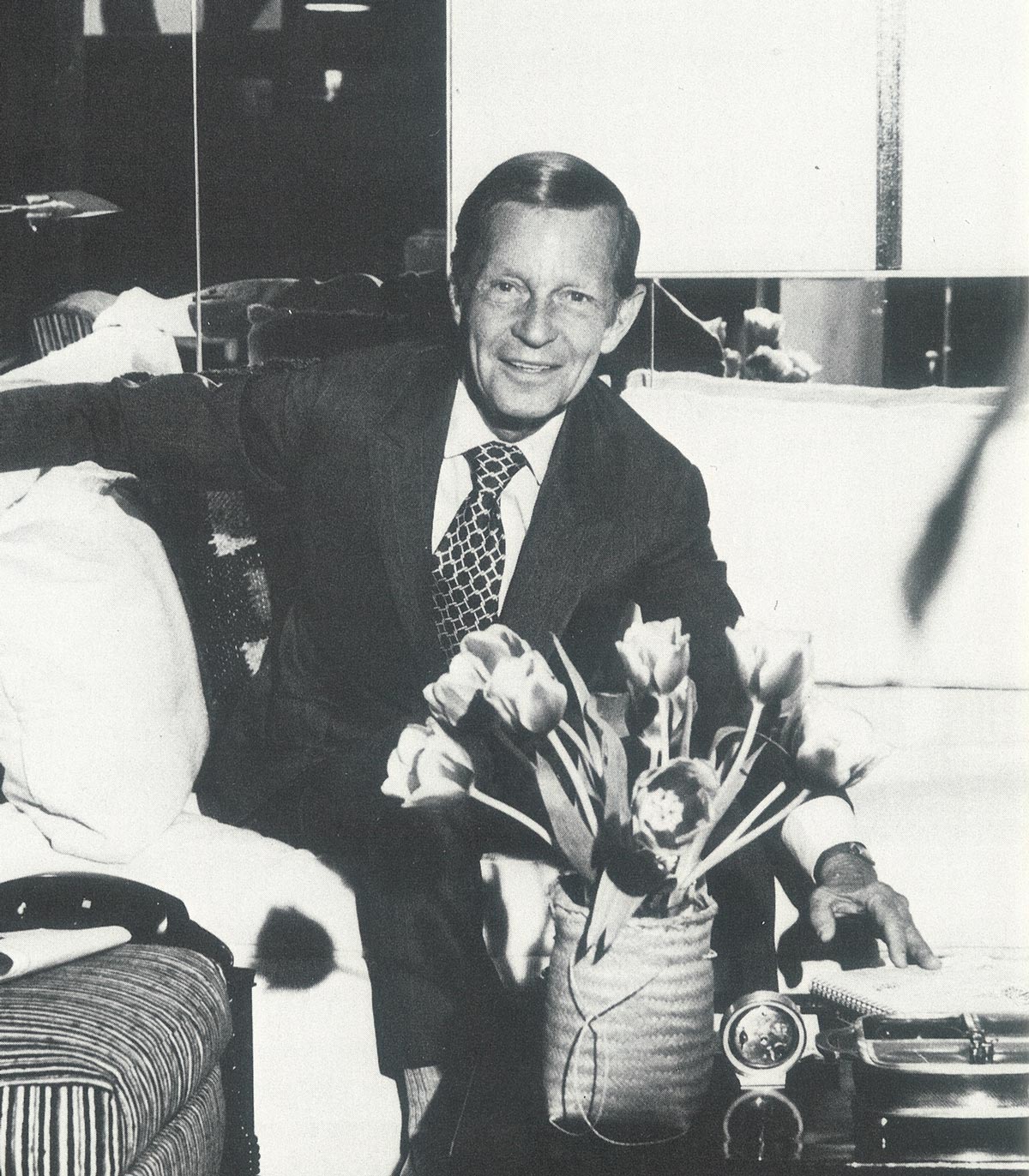

Billy Baldwin

The dean of indigenous decorators (he abhorred the term interior designer), Billy Baldwin was at once a classicist and a modernist. Though his aesthetic emotions were from time to time stirred by things Continental, in general he disdained the florid, baroque and rococo in favor of the clean-cut, hard-edged and pared-down. Among his early influences were Frances Elkins, perhaps the most sophisticated decorator of her day, and Jean-Michel Frank, whom he described categorically as “the last genius of French furniture.”

Baldwin’s own work was slick, in the positive sense: neat, trim and tidy—indeed, immaculate. It was also snappy: everything tailored, starched and polished—yet at the same time uncontrived-looking. Above all, it was American. “We can recognize and give credit where credit is due, to the debt of taste we owe Europe, but we have taste, too,” he declared. He would live to see his own name become a byword for exemplary American design.

For Baldwin, who was partial to plump deep-seated sofas and chairs, the ultimate luxury was comfort. “First and foremost, furniture must be comfortable,” he decreed. “That is the original purpose of it, after all.” He usually had it upholstered straight to the floor, believing that too many naked chair legs left a room looking “restless.”

Eclectic where furniture was concerned, he championed “a mixture of all nationalities, old and new,” but one of the canons he carried at the forefront of his mind was that there must be a connection between the various pieces. That connection, not surprisingly, was quality, in the name of which he favored pieces of contemporary design over reproductions of antiques. Unlike most decorators’, Baldwin’s first impulse was to use some of the furniture the client already possessed—”I do not necessarily believe in throwing out everything and starting from scratch.” The full atmosphere or mood of a room could never be achieved, he felt, without an “enormous personal manifestation” on the part of the client, which would serve in turn to enhance his own work. In fact, he confessed that he had “a natural interest” in women’s clothes “to the extent that they were going to be worn in the rooms that I was working on.”

Baldwin was well-nigh infallible in matters of scale, proportion and juxtaposition, yet he persisted in thinking of himself primarily as a colorist. “I suppose one could say that I almost started the vogue for a clear, Matisse-like decorating palette,” he told Architectural Digest in 1977. (Matisse himself he revered for “emancipating us from Victorian color prejudices,” and as a boy he had even been introduced to the artist—and by no less than Gertrude Stein’s great collector friend Dr. Claribel Cone.) Fresh, frank and forceful as Baldwin preferred his hues (he once specified a very dark green for a Palm Beach apartment, handing the painter a gardenia leaf that he had just spat on and saying, “This is what I want the walls to look like, including the spit”), one of his favorite colors was “no color at all.”

Other Baldwin staples were cotton (he was, he claimed, one of its “most active promoters since World War II”); plain draperies; white plaster lamps; off-white and plaid rugs; pattern on pattern; geometrics; corner banquettes; his own curved version of the low, box-based armless slipper chair; dark walls (his legendary one-room Manhattan apartment was lacquered a style-setting high-gloss brown);

Parsons tables wrapped with wicker (“I certainly made a lady out of wicker,” he once quipped); and straw, rattan and bamboo. His pet aversions were jumble and clutter, satin and dam-ask, ostentation of any kind, fake fireplaces and false books (real books he regarded as a capital decorative element).

Baldwin’s timeless triumph (he, too, considered it the coronet on his career) remains Cole Porter’s Waldorf Towers apartment, with its decisive library of Directoire-inspired tubular brass floor-to-ceiling bookcase-étagères arrayed against lacquered tortoiseshell-vinyl walls. Other cardinal clients included the Paul Mellons; Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis (for whom he decorated houses in Middleburg, Virginia, and on the Greek island of Skorpios); Diana Vreeland (whose vermilion “garden-in-hell” Park Avenue living room was one of his most audacious creations); the William S. Paleys (whose high-ceilinged living room in the St. Regis Hotel he covered in shirred paisley); Kenneth’s hair salon (a riot of color and pattern inspired by Brighton’s Royal Pavilion); and Greenwich’s staid Round Hill Club.

William Williar Baldwin, Jr., was born in 1903 to an old Baltimore family and grew up in a house designed by the eminent New York architect Charles A. Platt, where “I was given by my parents the present of the wonderful experience of doing my room entirely over, including the furniture.” After briefly studying architecture at Princeton and then grudgingly selling insurance in his father’s agency, he made the ineluctable leap into hometown decorating. By 1935 his work had caught the famous eye of decorator Ruby Ross Wood, who implored him: “I feel I need a gentleman with taste and I have found him in you, wasting away in Baltimore. We must get you away from there as fast as we can. There is obviously no work for you there. The house [you did for] Edith Symington stood out like a beacon light in the boredom of the houses around it. Will you take thirty-five dollars a week?” Baldwin moved to New York straightaway. “I was in revolt against Baltimore,” he later recalled, “a town in which there could not have been more than three or four French chairs. In New York there were thousands of French chairs—and lots of Rolls Royces so the traffic looked better.” After Wood’s death, in 1950, he branched out on his own, going increasingly out on the limb of “simplicity in every way.” Near the end of his life he wrote, “No matter how taste may change, the basics of good decorating remain the same: We’re talking about someplace people live in, surrounded by things they like and that make them comfortable. It’s as simple as that.”

Billy Baldwin retired in 1973, and a few years later this remorselessly social creature removed himself to Nantucket, where he had been summering off and on since childhood, to finish out his time. There he was exultantly confirmed in his lifelong belief that the greatest luxuries were also the simplest: the island’s “prevailing peace and privacy” and “that true, clear Atlantic light.” Billy died on November 25, 1983.

– Architectural Digest “Design Legends” January 2000